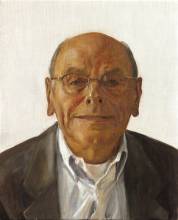

We would like to thank Mr. Felix de la Concha for letting us use this interview in our ”Documenting Wallenberg” project. The interview is a part of a larger series of interviews he has done with Holocaust survivors while simultaniously portraying them.

Q: What is your name?

A: My name is Gabriel Hartstein. I live in Burlington, Vermont.

Q: What city and country were you born in?

A: I am from Budapest, Hungary.

Q: Tell us about your family.

My parents were pretty poor. My father, who only had an eight grade education, was a superintendent of a small apartment building, and as such, he was in charge of having the heating for the winter as well as any kind of maintenance for the building. We lived in a one bedroom apartment, in the same building. So, he actually worked from the apartment that we lived in. There were only three of us at that time: my mother, my father and I.

Q: Was your family religious before the war?

A: No, they were, what we call, just barely practicing.

Q: Can you talk to us about daily life before the war? When did you first notice signs of anti-Semitism?

Hungary was a pretty good place to live even though there was a lot of anti-semitism, and there were a lot of laws, generated right after the World War I, that discriminated against the Jewish population. The Jews could not hold certain jobs, nor could go to the university, only like five percent of the people. But in the city of Budapest, where I lived, twenty percent of the people were Jews, and most of them were professionals and businessmen. It is kind of ironic that even though there were all kinds of restrictions against Jewish people becoming professionals like doctors, or writers, or teachers, that there were so many of them in Budapest. By law, they couldn’t study at the university, so how did it all work? Many of these Jews went to foreign countries to study. Actually, they went to Austria, Czechoslovakia, even Germany, which was pretty restrictive, too but later on, after Hitler came to power. Once they had finished their studies, they were able to come back to Hungary to practice their professions. How is it that they were not allowed to study, but they were allowed to practice? At that time Hungary was an agrarian country. There was not very much industry. While Horthy, the dictator who was ruling Hungary, was anti-semitic, he also wanted these Jews to come back to Hungary and modernize the country. You know, smaller farms and smaller cities weren’t even electrified. It was a country that had a lot of progress to do, and that’s why the Jews had kind of a haven, both anti-semitism and opportunities to advance in the country. It was in the interest of the Hungarian government to have Jews succeed. They couldn’t belong to organizations and so on, but anyway, on a daily bases, the Jews had a pretty good life in Hungary.

Q: How did you experience the Nazi takeover of Hungary? What were your thoughts, feelings, and reactions?

A: Well, I lived in Budapest and I was seven years old when the holocaust in Hungary started. The holocaust in Hungary lasted only nine months. The Germans invaded Hungary and arrived to Budapest on March 19, 1944. Since I was just a child, I really didn’t know what was going on. Up until then, I wasn’t at all aware of my own Jewishness, or my religion. I had friends that were Jews as well as friends that were non-Jews. As a matter of fact, on the day of the invasion, I found it very, very exciting because the Germans were parading up and down the street in their uniforms and tanks. It was like a military parade, so it was very interesting. The first day nothing was going on other than there were Germans parading up and down the street. Those of us who were children – you know that boys like to play with soldiers, that’s part of the toys of everybody – played live. We would put white gloves on and march up and down, trying to imitate the Germans. To tell you the truth, my parents didn’t know either what was going to happen. They were following the news and they new that it’s was a bad sign, but in terms of precisely knowing how it will work it took a little bit of time. The person who came to Hungary to implement the holocaust, the rounding up of the Jews, was Adolf Eichmann. He had already implemented the system for deporting the Jews to the concentration camps in other countries. We didn’t even know the words ‘concentration camps’, or anything like that.

Q: What changes did you experience?

Now, what I’m going to tell you is how the Germans set up the process of deporting Jews and taking them to the concentration camps. Like I said, nobody new the first step, or the steps that were about to follow; you know, the whole method. There was a law in Hungary according to which you weren’t allowed to listen to a foreign radio station, so the knowledge that people had about the war was very limited and it was controlled by the Hungarian government. Nobody could even anticipate what would happen once the Germans come in. People really didn’t know that the Jews and other minorities all around Europe, were taken away to these concentration camps. Some rumors were heard, because there were people who managed to escape the deportation or from one of the concentration camps, but the information wasn’t available instantaneously, as today. At that time, Hungary was an ally of the Germans. The government that existed in Hungary was a legitimate Hungarian government, not pro-Jewish, but not necessarily willing to cooperate with the Germans in taking the Hungarian Jews away to the concentration camps. But the tide turned against the Germans by March, 1944. and the Hungarians were starting to get cold feet because of the Russians. The Russians were advancing toward Hungary, and the Hungarian government didn’t want to be in the same situation it was in the World War I, when they were on the loosing side. Because of that, the Hungarian government tried to become a little bit more neutral and that’s why the Germans occupied it. They took control of the situation and started setting up the rules that the Jews had to follow.

The very first rule that directly affected all the Jews, was that we had to wear a yellow star. It was one of the signs that separated the Jews from the rest of the population. We had, one or two, maybe several weeks, to have the yellow star sown on all the garments that we were wearing outside. And why is it that every Jew had put the yellow star on? That’s because it was very easy to identify us, either through the police records or identification cards. The star made a very visible identification of the Jew, so all the neighbors now knew who the Jews were and we felt bad about it. It was a very discouraging and disturbing sign. That was the first rule that the Germans implemented.

Soon after that, there was another rule. The Jews had to move to a certain area of Budapest. By the way, I haven’t mentioned it, but we lived in Buda. Budapest is one city divided by the river Danube, so one side is Buda, the other side is Pest. Not too many Jews lived in Buda. But the rule was that all the Jews had to live in the Pest part of Budapest. And that area became the Ghetto. Every house in that ghetto was also identified with a yellow star on the outside of the building. By the time all the Jews were supposed to move to the ghetto, they didn’t fit. So, they moved into the houses, which were not encircled, but were very close to the ghetto, and were identified by the yellow stars. How did we get an apartment there? What you had to do is find somebody who was willing to swap apartments with you. My parents found somebody who had a one room apartment instead of a one bedroom apartment, and that’s where we had to move. To summarize, we had to wear a yellow star and we had to live in the specialized, specifically designated houses that were for Jews only. They called them Jewish houses actually.

At the same time when all this was happening, the Jews were taken away to the concentration camps. The Jews were picked up by certain criteria. The Germans would come to each of these buildings and look for people by criteria, as for example – age, health, etc. Those people who fit that particular criteria of the day, were taken away. We now know that ten to twelve thousand Jews were loaded into cattle cars and taken away to Auschwitz and other concentration camps, under horrible conditions. Ten to twelve thousand a day, seven days a week!

Another limitation that was implemented was that the Jews who lived either in the ghetto or in these Jewish houses, could only go out for two hours a day, from eleven to one – I think, to go shopping. Somehow my mother realized very soon that the prices of the food were such that there was one price for the general population and then for the Jews, when the Jews were allowed out for those two hours, the prices would double or triple. So, since we were poor and had very little money, my mother went out when she wasn’t supposed to be out on the street. She would cover up her yellow star with her pocket book. It was a terrible danger but she was willing to take that risk in order to reduce our food bill by half or by third. If you were found out, you were immediately taken to the police station and then taken away, whether you fit the criteria of the day or not. I can’t even fathom how she paid for it and how it is that she was never found out. At any moment, the police or the Germans could ask for your identification papers and if you didn’t have them with you, or if you were identified as a Jew, you were immediately subject to arrest.

Now, what kind of argument did they use so that people would go along and obey all the rules? You know, nobody objected to anything. After the war, people asked: ”How come that everybody went off like sheep? The Germans said ‘Do this,’ and people did it. How did it happen that the Jews were so easily picked up according to the plan?” Everything was going very, very efficiently. The Germans were never brutal within the city. They wanted compliance by the Jews so, they made all the rules very neutral. They weren’t threatening, and they were saying that the Jews were taken away into factories, for work, so that they would have an opportunity to earn money. They presented it like it was for our benefit.

My father was taken away to serve as a waiter, or something like that, for an officer in the Hungarian army. My father had a very bad accident as a young man and he wasn’t eligible for heavy manual labor. The Jewish men were mainly taken away to do labor, to repair the infrastructure that was destroyed by the bombs that fell daily on Budapest, dropped by the Russians and sometimes the allies. In that sense, my family was very lucky because my father wasn’t stationed very far from the Jewish house we lived in, and he could even come home once a week, so we saw him from time to time and we knew that he was not going to be deported.

So far, our personal situation wasn’t that dire because, other than the fact that we had to move to these Jewish houses, that my father was in a labor camp, and that my mother took extreme risks every day – being on the street when she wasn’t supposed to be outside, it was not as terrible as for other people who had been already taken away.

As time went on, by around October, in Budapest, there was a coup against the legitimate government, organized by the Arrow Cross. The Arrow Cross were the pseudo government and they were nazis. They were Hungarian anti-semitic nazis who acted like an army, supplementing the Germans. They weren’t fighting like the Germans, in the World War II, but their purpose was to help the Germans implement the deportation of the Jews to the concentration camps. And all my really, really bad experiences were associated with the Arrow Cross. The Jews who lived in the countryside or smaller cities were taken away very, very quickly. Budapest had twenty percent of the Jews, so it took a longer time, and it didn’t affect everybody equally right away. By October, life in Budapest was still manageable and we were hoping that the Russians would come and liberate us.

Q: Who was Raoul Wallenberg?

By the time of the summer of 1944. people in the United States realized that the Jewish population of Europe is being exterminated. So they wanted somebody to go to Hungary and try to save the remaining Jewish community, which was still substantial. They went to Sweden, because it was a neutral country in the war, to find such a person, and that was Raoul Wallenberg. He actually saved our lives. Even today, Wallenberg family is extremely influential in Sweden. They are industrialists, and at the time of the war, they dealt with arms and finance. Today they deal with lumber and they manufacture paper. Raoul Wallenberg wasn’t a diplomat. He was educated in the USA, at the University of Michigan. He became an architect, and his family was hoping that he would become part of the banking family. He didn’t really have a clear mission in life at the time when he was picked. And it’s very interesting, almost miraculous, because Raoul Wallenberg wasn’t the most obvious person to undertake such a mission. But he took it! And he said: ”OK, I’m going to go to Budapest, and I’m going to set down conditions that have to be met before I undertake this mission. One is that I am to be given diplomatic status and have authority to negotiate as a diplomat on behalf of the Jews.” Second, he wanted money in his possession to take along to Hungary, and third, he wanted the backing for this mission of the king of England. So those were, let’s say the three key conditions that he asked for. There were others but they were less, less critical at the time.

He came to Budapest and used his diplomatic power to make appointments to negotiate on behalf of the Jews. The first person, at least according to my readings, that he saw, was the foreign minister. The foreign minister at this time was a member of the Arrow Cross. The active collection of the Jews was the responsibility of the Arrow Cross, so if Raoul Wallenberg wanted to accomplish anything, he had to negotiate both with the Germans and with the Arrow Cross. Another thing was that he had to act fast. So, he arrives in Budapest and he invites the foreign minister to a dinner at his house, where they come to an agreement. Raoul Wallenberg had two key arguments. One was the obvious fact that the war was going to be won by the Russians and the allies, and the other was money, which he offered to the foreign minister in exchange for his cooperation. They agreed that the Jews who have relatives in Sweden ought to be protected from deportation and that he would issue a document called a schutzpass. Schutzpass is like a passport, a one way passport, which stated that the person that carries it has relatives in Sweden and when he or she has the opportunity to leave Hungary, Sweden will welcome him or her. Getting this kind of document was a life saver. It was like a passport that couldn’t be used at that time because Budapest was surrounded by Russians, but nevertheless it was good for the future. Also, Raoul Wallenberg suggested that he buy certain buildings and designate them as safe houses for the Jews who had some Swedish connection. Theoretically these people would move into these buildings that were like an extension of the Swedish embassy or the Swedish consulate. The Arrow Cross, or the Germans, or the Hungarian government, nobody would allow to take away these Jews. They decided that about five thousand Jews would qualify for this.

Now, the question was how he was going to find the Jews with relatives in Sweden. Raoul Wallenberg thought, and he said: ”Well, the way to find these Jews, since I can’t advertise and I can’t do it word by mouth, is to go to those Jews who are being transported out to Germany, to Poland, or to where the concentration camps were. Those are the ones that are most vulnerable.” A well known place where they collected all these Jews who were on their way to the concentration camps, was a brick factory. It wasn’t a functioning brick factory so it was an empty place. It was like a temporary concentration camp, in a way. The Jews were taken away from all parts of Budapest and they were collected in this brick factory. Their next step would have been to actually walk to the Austrian border where they could be loaded onto cattle cars. So, Raoul Wallenberg goes out to the brick factory and says: ”I am Raoul Wallenberg, the representative of the king of Sweden, and I want to go inside and address the Jews who are in this brick factory, and take out all the Jews that have Swedish connections.”

Q: Did you have any contact with Raoul Wallenberg?

A: Well, I never met Raoul Wallenberg personally, but my cousin did. I had indirect contact with him.

My cousin was in that brick factory on that faithful day when Raoul Wallenberg showed up. In the middle of the night there is commotion, and all of a sudden, somebody comes in and addresses the Jews and he speaks to them as human beings instead of using rough language. She hasn’t heard anybody who speaks to a Jew in a kind way. So even though she didn’t know who Raoul Wallenberg was, that was the most reassuring thing for her to have somebody speak to that crowd as human beings – with respect and with optimism. Raoul Wallenberg asks that anybody who has relatives in Sweden or anybody who lives in Sweden, come forward and show a document that proves that they have relatives in Sweden. Well, you know, this question that he asked was really unreal because who would go around carrying a piece of paper or a picture or anything of some distant relative in Sweden. My cousin and few others realized that if they showed any kind of a piece of paper that might be their chance to be saved. So, she goes into her pocket and she shows a piece of paper to Raoul Wallenberg and he looks at it and he says: ”It is OK. You can get on a truck, which is outside the brick factory.” She grabs her mother’s hand and they leave. Then, other Jews started doing the same thing because they saw that they would get out of there.

Q: What was in that paper?

A: It was nothing! It may have been toilet paper, it could have been just a piece of paper. But you know, those Arrow Cross guys were plain soldiers and Raoul Wallenberg was so convincing to these people. He had authority, so they complied. My cousin went back to Budapest on one of these trucks and she was actually taken to the Swedish embassy, where she got her official schutzpass, with her name and picture on it. She, then, obtained schutzpasses for other members of her family, including us. It took her a while to deliver it to us, because we were still in this Jewish house.

Q: How did Wallenberg save you and your family? Tell me about your experience with him. How much were you aware of the situation?

A: I don’t remember the date, but it was probably November of 1944. The Arrow Cross soldiers, came into our building, and told my mother that both of us, my mother and I, should come down within an hour, with very little things of our own, because we were going to have the opportunity to go to a doctor and have a physical exam. There were no more people left, other than children and mothers, in our building. So we were the last ones who could be possibly taken away. There was no place to hide, there was no place to go, and my mother and I went down. My father was still away in this labor place where he was working for that officer, so we had no way of talking to him or saying goodbye. We formed a large group with people coming from other buildings, and we were marched to a large square. Maybe it wasn’t very large, but it appeared awfully large at the time, because there were hundreds and hundreds of Jews. We assembled there and one of the Arrow Cross soldiers used a bull horn to shout out orders, as to what we should do next. He started screaming that all the children have to go to the right side of the square and the mothers ought to stay in place. And from best that I can remember, just about all the mothers who were there told their children to go to the right side, except for my mother. She said that I shouldn’t move. Soon they noticed, and one of the soldiers approached us, yelling at my mother for not following orders: ”I’m going to kill you and I’m going to beat you to death with butt of my rifle!” My mother said to him: ”It’s OK, but just make sure that you kill both of us.” Then more soldiers came to see what was going on, and they tried to pull me one way and my mother the other way, and I still can’t explain how it is that two or maybe three Arrow Cross big guys couldn’t rip me out of my mother’s arms. She was a little woman, but she was a kind of person, who would go left if the authorities told her to go right. She always did the opposite. She knew more than she let it believe. She was a survivor. So they agreed that I go with my mother. We started marching. There were probably six to eight people in a row, but I don’t know how many rows there were. Endless rows. And we march, and we march… My mother knew that we should not get to that brick factory because it was at the outskirts of Budapest. She knew that if we go outside of Budapest, it was going to be much more dangerous. We would be much more exposed than within the city. So she tried to escape. She went to the right of the row, to the left of the row, and people started complaining about her, that we are all going to be in trouble because of her and she was a troublemaker. She had a lot of grief from the other Jews who willingly went and they didn’t know where they were going but they did it without any objection or any opposition. They felt safe as long as they were doing what they were told. And they were mad at my mother. All the time she gripped my hand and I was supposed to follow her. At one point she sees a car, pulls my hand and we end up hiding behind a tiny little car – all cars were tiny, they didn’t have SUVs or anything like that. Of course, we were spotted immediately, because there were a lot of Arrow Cross people in front of the car, and we had to go back to that row of marchers. We would have continued but, by some miracle, my mother fainted and fell straight to the pavement. The Arrow Cross soldiers gathered around us, not knowing what to do. Finally, their leader gave one of the Arrow Cross guys direction to take us back to our building where we came from. And the chances would have been that the following day or in the subsequent days we’ll be taken away once more, because there were still plenty of Jews in the ghetto and in the Jewish star homes, to be taken away. And so, actually, it wouldn’t be any loss to any one of them to let us go back. It would have been anyway just on a temporary basis. But literally the next day, my cousin who was saved by Raoul Wallenberg, gave us the schutzpasses. We got three schutzpasses: one for my mother, one for my father and one for me. Once again, by some miracle, we delivered one of those schutzpasses to my father, so all three of us were protected.

Now, from the story that I told you, it was a miracle that my mother fainted and that they got her back to the Jewish building, and my cousin came and gave us the schutzpasses. All that is a miracle that I have no way of explaining. But I will have to tell you that I never saw a person that came back from that march we would have been on had my mother not fainted. These were called the death marches. When I speak to students, there is a description about what kind of faith awaited those people who went to the brick factory, and then had to march to the Austrian border, in the middle of the winter. I’m talking about November. Some grandmother who survived the camps and was one of the death marchers writes about it. I am very much affected by her story and I’ll tell you why. She tells how they were marching and how they didn’t have any food, and no water, no fluid, and at night, they got relief from marching and they had to lay down on the ground. It was so cold that some people actually died frozen to the ground; especially elderly people. And in spite of their hunger and lack of water they had to continue the following day. One day in this march, a farmer came toward them with a bucket of water and a ladle, and the Arrow Cross soldier yelled at this farmer: ”If you make one more step, I’ll shoot you!” This was outside Budapest and it would have been no problem for this Arrow Cross guy to shoot him. But the farmer said to him: ”Try me.” And he went ahead with a bucket of water and a ladle, and he gave people to drink out of that ladle. And the reason that I always find this story very, very moving, and tell it to the students is that there were people who saved other Jews. This farmer probably never saw a Jew before in his life, and even though he had his family to take care of, which is why he could have easily just turned around with his bucket and with his ladle – he didn’t!

I don’t know where these people get all this heroism in them, and what’s amazing to me is that there were people at all who stood up, who were moral enough to stand up for these people. It was not for money, not for any financial reward, but it was only the moral strength, or the way they were brought up, or their religion. I don’t know what it was, but today we are immune to that kind of thing. Yet Raoul Wallenberg and this farmer, they exposed their lives every day to save Jews. I tell this story of rescue because it has so much significance to me. People did these things without questioning, and it would have been so easy to find one excuse why not to do it. I had to tell you the story of the farmer because it’s a model for me to teach the students today as to what people did, you know who weren’t as, and I use it really the word sophisticated in a kind of a satyrical way because they didn’t have internet and they didn’t have cell phones and they didn’t have all the modern conveniences but they just knew what to do at the critical time, at the right time to save people. And that’s the reason some of us, including me, are around.

Q: Did you live in a safe house? What was the experience like?

We moved to a building, which was like an extension of the Swedish embassy, and the address of which was printed on our schutzpasses. We were designated an apartment, same place where my cousin was, and it was so crowded that we had to lay down head to toe. There was no furniture and there was only one bathroom for so many people. I don’t know how we managed. By today’s standard, I’m wondering how so many hundreds of people were able to get along and didn’t kill each other. But there was no violence or anything like that. I also remember that we had some limited amount of food. Daily, more and more people came because Raoul Wallenberg and people from the Swiss embassy just kept printing those schutzpasses, and kept going to those marchers, or back to the brick factory, or all the way to the Austrian border and grabbing the Jews from the trains. I think the number was maybe fifteen thousand, or so. And, so we were kind of safe being in these protected houses. Arrow Cross couldn’t take us away from there. But it appears that the different schutzpasses had different strength. I don’t know how the Germans or the Arrow Cross knew that. One day, they came into our protected building and they asked to see the schutzpasses of each one of us, and they started separating us into two groups. Even though we all had schutzpasses, one group was taken away from that building. They were marched out, and nobody could say a thing, and nobody knew why or what the criteria was. My family stayed safe, but our story doesn’t end there.

Q: How long did you stay in the safe house?

I have to emphasize again that my mother was a survivor, even though kind of a difficult woman who did things that were not rational. When she saw that some people were taken away from the safe houses, she said: ”I’m going to go out, back to the old neighborhood where we lived, and I know a person that will do something for us.” Now, why was this irrational to begin with? Here she is, a Jew with a star, she has to take the trolley from Pest to Buda, because it wasn’t a walking distance, she has to go back to Buda to the building where my father was the superintendent and go to one of our neighbors. He or she may have been a dissatisfied neighbor who had it in for my father because maybe the heat was not OK one day in the winter, we didn’t know. But my mother had this feeling about a particular woman from our old apartment building. I know all this from my mother, as she was telling the story. She got in, she rang a bell, the woman opened the door and my mother said to her: ”Mrs. Saylai, you must save us.” The woman almost fainted. She told my mother to never, ever come back, but she quickly jotted down the name of her brother in law. She said: ”Go to this place and he will save you.” So my mother took that address, and she went to this man who happened to be a well known writer of plays and novels. His name was Remenyik. I don’t even know if my mother knew how famous he was because, first of all she was born in Poland, and second, she wasn’t a well read person. She had four grade education, even less than my father who had eight grade education. So she went to this Mr. Remenyik at his apartment, and said: ”Mrs. Saylai sent me, gave me your address, you must save us.” I can’t understand it. Here is that woman, coming into the building to the apartment of this famous writer and asking him to save us. And he told her that it was OK, that she should come back in a few days, and that he would have documents ready for her and give her further directions. By the way, in all that time since that first time that the Arrow Cross had come to our safe house and separated people, they didn’t come back again. But my mother was afraid that if they could come once, they could come a second time and she felt she needed more protection. When she went to see Mr. Remenyik for the second time, he gave her false documents that somebody made, and Remenyik payed for them. The documents said that we were Christians. Our names were changed from Hartstein to Harsanyi, which is a typical Hungarian name. We had now a Hungarian name and false papers saying that we came from the farms outside Budapest to Budapest to escape the terrible rushes. He also provided us with an apartment. We were supposed to tell our new neighbors that my mother was the maid of the Remenyik’s. That’s how we, all of a sudden, appeared in a strange building, in a strange apartment, close to Christmas 1944. We didn’t ask any questions. Later on, after the war, we discovered that Mr. Remenyik was saving in his own apartment ten Jewish families.

Q: How did you survive until the end of the war?

We are in that apartment, and every day planes are coming, bombs are falling, and buildings are destroyed. We tried to stay in that apartment in order to avoid questions from our neighbors, even though everybody went down to the shelter, in the basement. But we sure enough brought attention to ourselves by not doing what everybody else did. One day, the doorbell rings and there is a neighbor who doesn’t know us, but he says to my father: ”Do you have any document that you tried to register for the Arrow Cross?” My father says: ”No.” This fellow says: ”You’d better go to register.”

By the way we weren’t wearing Jewish stars, any more and we could go out in the street any time, because we had documents that we were Christians. I was taught a new name. At that time, I didn’t know what a Christian was, I just knew what a kid was. We tried to avoid as much as possible drawing attention to ourselves, so my parents allowed me to go to other people’s. If somebody was in their apartment, I was told that I could go and play with their kids for a little bit and then I had to go home. They didn’t want me to expose myself too much, because I could have said the wrong thing.

So, my father had to go register, which implied a physical exam. He was scared to go to the police station. Even though my father had false documents, there was one thing he couldn’t explain about himself, no matter what document he had. In Hungary, I don’t know about all countries in Europe, but in Hungary, if you were circumcised you were a Jew. This situation was even worse than being hit by a bomb, because, if they discovered that my father was a Jew, potentially we could have exposed Mr. Remenyik and ten other families that he was hiding. Before my father left to go register, he gave us instructions that if he didn’t come back within a certain time, we should go immediately to Mr. Remenyik. But, within couple of hours my father showed up, and told us the story that I am going to tell you. He went to the first guy that he saw, who was some kind of Arrow Cross clerk, and said: ”I came to register for the homeland.” The guy asked about my father’s personal data and typed it all up. Then he told him: ”OK, sit over there and you are going to go to the doctor for a physical exam.” My father sat down on the floor and he said to this guy: ”Look, you don’t have to be a doctor to see that I couldn’t really go to the army, I will just be rejected if I go in there.” So the guy wrote down something, I guess it was a document that he filled out, and my father got an exception that he didn’t have to register till February, 25. That was great. Now, he could go back to the apartment and show that he tried to register and they gave him an exception. This document that he didn’t have to be registered until February 25, gave us further opportunity to be a little bit more safe, and it also gave us a legitimate reason to give up the apartment and go down to the shelter because we were no longer threatened by somebody asking us funny questions. We felt that we were protected against all eventualities.

When we lived in the shelter, people were listening to the radios, but not foreign stations, because you couldn’t get short wave radios. Sometimes, the Russians advanced, sometimes they were pushed back. It was January 15, in the middle of the night there was a big commotion at the entrance to the shelter, people speaking foreign languages… These were Russian soldiers who came in, and they were in charge of our street. We knew at that point that we were truly, truly safe. We were liberated. It was in the middle of the night when the Russians came, so the following day we went out and people were on the street. All kinds of people. Street was filled with Russian soldiers at that time, with machine guns and all that, but we felt safe, because they weren’t Germans, they weren’t after us. We went back to see how many people were alive from that Swedish building, like my cousin and all the relatives that we had. My father ran into somebody that he knew from before the war. So, this guy said to me: ”Well, what’s your name little boy?” I remember that very clearly, and I asked my father which name I could tell him, because I knew I had to be very careful, because they drilled it into my had, that I should call myself Horsanyi Gabor. My father told me: ”You can tell your real name.” That was such a big deal for me as a child, as if I just got the Olympic medal or something. It was really amazing that it’s engraved in my mind.

Q: After the war, what happened to Raoul Wallenberg?

We were liberated on January 15, by the Russians, and from the time that they liberated us they were only advancing, advancing, street by street. Budapest wasn’t liberated all at once. There was no way of taking the Jews out anymore, because Budapest was totally, totally surrounded by the Russians. Yet, there was still close to hundred thousand Jews left in the ghettos. So the Germans came up with a plan that they were going to make everybody move into a building within the ghetto, and they were going to dynamite all those people within the building. Raoul Wallenberg heard about it, he contacted the commander of the ghetto and he used the exact same arguments that he used with the foreign minister and maybe many, many times in between when he wanted to save people. He said: ”Budapest is all surrounded by Russians, and they are going to be here any day now, and you have a chance to save a 100,000 Jews. If you don’t do that, you are going to be a war criminal and I’ll be the first one to testify.” The commandant thought about it and agreed with Raoul Wallenberg’s proposal. But then, a tragedy occurred. On January 17, or two days after my life was saved, my parents’ life was saved, and other people were saved, there is an officer who comes to Raoul Wallenberg and says that general Malinovsky – who wasn’t in Budapest, but somewhere, in some small city behind – wants to see Raoul Wallenberg and that the officer is going to give him a ride. Raoul Wallenberg had no choice, he got in the car and the car took him to this general, and that was the last time that Raoul Wallenberg was seen.

He was kidnapped, was sent to Russia, and in the ’70s people who were coming out from the Gulag were talking that they remembered being in the cell in Siberia next to some Swede. There is no conclusive or absolutely certain evidence that it was really Raoul Wallenberg. I don’t know, and I read several books about how he was kidnapped by the Russians, tortured, sent to the worst place in the Gulag and if he survived, he may have died in the forties, he may have died in the fifties… nobody knows. And even now that the Russia is no longer the communist system, theoretically they allow people to see the papers, nobody can say for sure when Raoul Wallenberg died and why he was kidnapped. There are some speculations as to why he was singled out and why he was a threat to the Russians. First of all, Stalin was so paranoid and the Wallenberg name may have been have been a threat to the Russians. They didn’t want any westerners in Eastern Europe, or certainly in Hungary, because they wanted to have total control so that they could establish communist regime.

Q: How did you move on with your life? How did you come to America?

A: In 1948 the border was still open between Hungary and Austria, so people could leave. But by 1950 all the borders were electrified and nobody was leaving. My parents never told me the real truth, but I think they have been dealing with an official in Hungary, and most probably bribed this person, so that my mother, me, and my ten years younger sister, who was born after the war, should be expelled from Hungary. It was a very unusual thing. In order for that to happen, my parents had to get divorced first, and because my mother was born in Poland, the three of us became what they call ‘homeless’, without citizenship. In that way we could be expelled from Hungary. We had fifteen days to leave the country, and the only place we could go was Israel. In order to get some dollars for our trip which were like a black currency and nobody was allowed to handle them, we turned for help to one Jewish organization, something like a rescue operation, that helped people right after the war. I found out that we were going to leave just few days before our departure. It’s funny how during the German occupation and the Holocaust my parents trusted me, but in this particular case, they didn’t. They held the whole thing secret until a week before we left. They said: ”You are not going to go to school anymore, and you are not allowed to go out on the street. You are just supposed to live incognito at home until we leave.” On September 15, when we had to leave, we went out to a railroad station, took a train to Vienna, but when it came to the border nobody had permission to get through the border, so all the other people had to get off. I don’t know, they weren’t necessarily going to leave, because nobody could leave. They had their own reasons for being passengers on that same train, but the three of us, we left, and we arrived in Israel.

Israel wasn’t a great place to live in 1950, the food was all rationed, clothing was rationed, bread wasn’t. I didn’t speak any Hebrew. I was sent to school and I don’t know how I learned Hebrew. I didn’t take private lessons, I just picked it up from kids. There was no housing for new immigrants so they lived in a refugee camp. My mother took the two of us to an aunt, actually one to one aunt, and the other to another aunt. The three of us were separated into three homes, and people lived under very primitive conditions. Israel wasn’t a modern country. It was kind of a backward country that was absorbing a lot of immigrants from various countries that wanted to go there for idealistic reason. But we lived out in the west. I mean, not American west, but in Israel. It wasn’t under communist control. My father suffered an awful lot because we left Hungary. They called him a traitor, and they wanted to expropriate his apartment, and send him to some village without anything to do. It was very difficult for him. And the people who made it so difficult for him were probably the same people who used to be Arrow Cross under the German rule. They became the most ardent communists under the communist control. You know, those people change positions and they become extreme no matter who rules or what system is in charge.

While we were in Israel we were waiting for a visa to get into the United States. I lived in Israel from 1950 to 1952. From 1952 to 1955 I lived in France, with an uncle of mine. There, I went to school and studied radio repair. In 1955, I came to the United States legitimately, after I had obtained my visa. This cousin, who once saved my life by getting us the schutzpasses, was in the United States as of 1948. She made sure that I get a decent education. She selected a high school for me, a very practical high school, where I could learn at an accelerated rate, which I did, and then I went to university and I became an engineer. I went to Hunter College, which was part of the City College of New York. And then NYU, New York University. I worked in the semi-conductor trade for thirty almost forty years. I moved to Vermont because I wanted to work for IBM.

Q: Did you experience any anti-semitism when you came into the United States?

A: Yes, I did. But I don’t feel threatened by it. I don’t know what it is here that gives me that kind of freedom. I usually explain it with separation of religion and state in this country, and I feel that’s a very strong principle. It’s a totally different experience than what I feel in Europe. First of all, in Europe I feel right away a little bit self-conscious about my Jewishness. Maybe because I went through those difficult periods in Europe. Maybe in Asia I wouldn’t feel that way.

Q: You visit schools, share your story, and teach people about Raoul Wallenberg. When did you begin doing so and why?

A: My cousin Suzan, this cousin to whom I keep referring, was part of a group that organized Raoul Wallenberg committee, which publicized his life, his contribution, and his heroism. This group of Americans tried to bring pressure on the United States to try to find out what happened to Raoul Wallenberg and make it known to public. So, she spoke wherever somebody invited her. She spoke in Australia, in many places, but mostly in the United States. She spoke until the day she died. She spoke with passion about Raoul Wallenberg, the greatest passion. She wanted people to know not just about her experience with him, but about all Raoul Wallenberg’s accomplishments. Since then, a lot more people know about Raoul Wallenberg. Today, there are memorials in various countries, but if you ask people if they heard of Schindler, you learn that just about everybody knows of him, because of the movie ‘Schindler’s List’. But there are other holocaust stories. I don’t know if Raoul Wallenberg is more heroic than others, but he is certainly significant. It’s a funny thing that somebody good didn’t direct a film about him. There was a TV series about him and it just wasn’t good; it was too Hollywood. It didn’t get the essence.

When my cousin died, I started speaking about my experiences with the holocaust which includes a story about Raoul Wallenberg. Actually, my cousin has been my inspiration to continue her legacy, because it’s important that people know about it. That is why I’ve been doing it for fourteen-fifteen years, already. The students react well, the teachers react well, and they invite me back. Those times are worth remembering. For example, I tell the students that one of my greatest pleasures, that I can have on a daily basis, is taking a shower. Students cannot understand that, because, today, you can always take a shower. But you know, during the war I couldn’t do that. My hear was full of lice! And, so you know, my values are a little bit different. But one thing is for sure, in the United States, I feel very free to talk about my experiences, my heritage and I’m glad to share it with students.

Q: How do you feel about the representation of the Holocaust in the movies and books?

A: Raul Hilberg was a great scholar of the Holocaust and just before he died he was on a talk show about the Holocaust and about his life. I don’t know, he was pretty sick and maybe they tried to get that interview before he died, I don’t know. The book he wrote is a serious book with statistics, and that is the first basic book that was written about holocaust. It was scholarly work. And he was an extremely brilliant guy. It is not my interpretation, all the scholars look upon him as the Einstein of the holocaust. In that interview, Raul Hilberg says that in 1960s, when the first book was published, he couldn’t get anybody interested in it. Here and there maybe, a movie appeared where the Germans are always the bad guys, and the guys that are hunting them are the good guys – that kind of thing. When I speak to students at schools, and ask about their reaction to ‘Schindler’s List”, they say: ”Well, it’s a great movie.” If that’s their only reaction – good guys versus bad guys – it disappoints me. Now, college students react differently. They are more serious.

Q: What kind of questions do students most frequently ask you?

A: Their questions are always the same – what was my experience. I think that’s it. You know, they relate better to a person than the chapter in a book. That doesn’t mean that they are not interested in the holocaust. Then I try to draw parallels between all the atrocities that are happening every day in the world. There are a lot of atrocities.

Q: Is there anything else you would like to share with us today?

A: I was much younger when I saw ‘The Great Dictator’ by Charlie Chaplin, in Hungary. It was the first time that I saw a Jew on screen who was the hero. There are two sides of the story. One is the holocaust, and the other part is just a human part, but nevertheless the hero is a Jew… whether he gets dressed up as Hitler. In Hungary, I never had the opportunity to express myself as a Jew, because I never trusted the people around me. There was so much anti-semitism around, so I would never talk about my experience or even myself as a person, and I had nobody to identify with. But when I saw the movie, I saw a Jew being the hero of the movie, and it happened to be a very important experience. It’s like a black person who takes pride now about Obama being the presidential candidate. Where I can take pride… a black person today can take pride of the fact that another black person is running for the highest office. And it’s that kind of a thing.

Transcribed and editted by Vesna Vircburger