Q: What is your birth name?

A: My birth name is Eva Brust.

Q: What is your married name?

A: My married name is Eva Cooper.

Q: Where were you born?

A: I was born in Budapest, Hungary.

Q: What is your birth date?

A: I was born on March 18, 1934.

Q: Where did you grow up?

A: I grew up in Budapest until 1947, when we came to the United States.

Q: Will you tell me about your family?

A: We were a small family – I am the only child – but we had a large extended family. My grandmother had many siblings, and they had husbands and wives and children. I am the first of the generation of grandchildren.

My parents and I lived in the best part of Budapest, and I lived in a very nurturing, and I guess, affluent family. My grandparents and my parents were university educated. My father was in a wholesale paper business, and my mother was a European lady, a housewife. My grandfather was in the watch business, and he was also very successful.

We had a household staff, which was a very popular occurrence in those days among the more comfortable families of Budapest. My parents traveled a great deal; we summered at the lakes in the suburbs of Budapest. I had a nanny, and I had an English tutor who taught me English. I also had a French tutor, so I was quite fluent in many languages, but I no longer am, unfortunately.

My early life was free, really, from any bad thought. I went to school, I had friends, and our world was kind of turned upside down in 1944. I was 10 years old. Up until then, I had a really wonderful life, as did my parents, even though, after 1939, they had become very much aware, as most intelligent people had, of Hitler’s intentions and his growing influence.

Q: What kind of school did you attend?

A: I went to, what we in the United States would call, a public school. I went through four grades in the elementary school, and then I went to the regular school, called gymnasium. It was a very interesting school; we divided up for classes in religious education. The Jewish children went to one class, the Protestant children to another and the Catholic children to another. That was the religious integration.

Q: And you studied your religion during those classes?

A: We studied, in our case, Hebrew and the history of Judaism. It was friendly, and there were absolutely no issues. After religion class, we students got back together, and we were all friends.

Q: What was your religious upbringing at home like?

A: We belonged to the big temple on Dohany Street – I think it is the largest temple in Europe, if not the world. It was a Conservative synagogue – there was no Reform movement at that time, and I did not know anything about Orthodoxy or the more religious aspects of Judaism. We were very traditional; we celebrated all the major holidays with our extended family.

Q: What were the first signs of anti-Semitism that you noticed?

A: I did not notice anything anti-Semitic until much later because, first of all, we were a comfortable, upper class family that enjoyed certain virtues because of the money. Also, my father was very much involved in the Jewish organization and had access to much more information than a lot of people.

There was no obvious discrimination, certainly not at my level, but around 1939, my father was definitely becoming aware of anti-Semitism. By that time, rumors about labor camps had started, but a lot of people ignored them because they seemed so preposterous. And actually, even though Horthy, who was the prime minister of Hungary, had a reputation for being anti-Semitic, he was also extremely friendly with the affluent Jews, especially the professionals.

My grandfather was much more concerned about Hitler than most people, and he decided to go away. He left with my grandmother on a supposed ”vacation” to the United States in 1939 and never returned. He had tried to talk our family into leaving as well.

Q: So, even though your father was becoming aware of what was happening, he did not convey it at home?

A: No – he probably did to my mother. My parents, even when things got worse, were very much responsible for me being fairly well adjusted. They always protected me and did not act like the world was coming to an end, even when it seemed like it was.

My father was aware of the situation; he was constantly meeting with Germans and Hungarians, trying to get us as much information as he could. And when my grandparents left, it had a major impact on our lives.

Q: And you did not know why your grandparents really left? You thought they were going on a vacation?

A: Oh, yes. That was the story. Actually, the reason my grandfather said that was because my grandmother never would have left her children – my mother and her brother – or me – otherwise. As a mother, she just wasn’t able to leave the whole family. She did not realize that her husband did not plan for them to return. He made provisions: he took money to Switzerland, and since they were in the watch/jewelry business, he took items from there. My grandfather very much planned for what he thought was going to happen – and he shared those thoughts with my father. But a lot of people thought that the danger would pass.

Q: When did you actually realize what was going on?

A: Probably in 1942, I think, when my father was taken to a labor camp. It was not a concentration camp, but it was outside of the country. The Jewish young men were taken by force to labor camps and made to do heavy-duty labor. I am not actually sure what kinds of things they were told to do – build things, move bricks…?

I know that a kind of tension appeared in my household in 1942, especially when my father was taken away. My father must have been very old – he must have been in his 30s at the time. There was a 12-year age difference between my father and my mother. My mother was obviously concerned and was always trying to contact people to ask them if he was OK. She was always trying to find out where my father was, and at some point, she was able to visit him and take him some warm clothes, some food products, and find people to make sure he was taken care of.

My mother met a young, 18-year-old man whom she asked to take care of my father. She also gave this man stuff to take to my father when she could not see him. My mother knitted my father items out of angora – things you wear under your underwear to keep you warm during the wintertime. It is funny because this young man ended up leaving for the United States many years later. He just died at the age of 90. He was very active in Israel, doing a lot of good stuff.

Q: How long was your father in the labor camp?

A: My father was there for several months.

I do not remember if my mother told me these things at the time or not. That was in 1942, and I was eight years old, so I do not really think she would have shared details, but she did explain to me why my father was not there. But she was always very cautious not to scare me.

The hard part for my mother was explaining to me when he was going to come home. My mother always said he’d be home ”soon,” and that ”Afterward, he’ll be fine. It is something he has to do.” I was very close to my father, so I did not like him being away.

Q: After your father was taken away, what happen to your mother?

A: My mother kept busy by working, going to my father’s business. My mother was highly educated, and even though she had never worked, there was nothing she could not do. She went into my father’s business and kept the household going. We had a cook and a driver until early 1944, and until that time, our household more or less ran the same as it had before – except it was a little bit tenser.

Q: What happened when your father came back?

A: When he came back, life went back to the new ”normal,” which was a little more worrisome because, while he was away, he got much more information. Also, some people from the labor camp were actually taken to a concentration camp and did not come back.

My father, as I mentioned before, was very active in the Jewish community – not the synagogue but the community. People who were influential and knowledgeable about what was going on actually met with Adolf Eichmann to negotiate how much money the Jewish community had to give him in order to get people off the list and prevent them from being taken to the camps.

Q: Do you know what happened at the meeting?

A: I had no idea who Adolf Eichmann was or what they were talking about, but I remember very clearly that my father said how charming he was. Of course, Adolf Eichmann was impeccably dressed and clicked his heels and shook hands and acted like a perfect gentleman, and all his discussions were pure business.

Q: Did Eichmann accept the offer?

A: Yes. I do not know, in reality, how many people were actually saved.

Q: German soldiers arrived in Hungary in 1944. How did your family manage that?

A: My birthday is March 18, and in the late afternoon of that day, 1944, we were having my 10th birthday party at my house with my favorite foods: hotdogs and ice cream. A lot of my friends were there. A lot of my friends were the children of my parents’ friends. The others were my school friends. There were also a lot of nannies at the party because they brought the children and then picked them up. The adults in attendance were my parents’ friends.

Then we heard marching and drums and a kind of weird noise. We lived on a street near a major boulevard, so we looked out the window and the Germans were occupying – which was expected because all of the neighboring countries had already been occupied. Budapest, Hungary was the last eastern European city to be occupied by the Germans.

So the Germans were marching in, and I was not happy because everybody left very quickly, before my cake. At the age of 10, I did not care about the marching people – I cared about my birthday. So, again, my parents comforted me, and we opened some presents. Then everything started to be weird; and I use the word ”weird” from a child’s point of view. I certainly had no clue about anything that was going on politically, just that it was impacting my little life.

Q: What kinds of changes did you notice after the German occupation?

A: Information came out about the rules and regulations regarding Jews, and it was all over the papers. One of the first major changes was that every Jewish family had to fire or let go their household staff, which had a major impact on my family because there were three of us, and we had a nanny, a cook and a chauffeur. It was a major change in the household dynamic. They were all wonderful people, really devoted to our family. Subsequently, they bought us food on the black market and got stuff for us when it was no longer available. That was the first change.

The second change was that every Jew had to a wear a yellow star – in a very specific way and place – and not ever appear on the streets without it. So that was weird. In one way, I guess, it was almost amusing for me, but then I realized it was not amusing and how serious the consequences could be for people caught not wearing the stars.

The next change was that Jewish houses were designated. Because of my father’s influence in the community, we were able to stay in our building, and it was designated as a Jewish house. The gentiles living there had the option to stay or move out. We did not have to move out of our apartment, but every family could only have one bedroom. I moved into my parents’ bedroom. We were fortunate because we could select the people who were to move into the other rooms, and we asked friends and families to move in with us. That was kind of exciting from a child’s point of view because, being an only child, there was a buzz about having other people and their children with us.

One of my parents’ best friends moved in, and her husband was an attorney, and their boy was my best friend – we had grown up together. So that was very exciting. The father wrote funny little poems, and he put them in every room. For instance, he wrote one about making sure to put the toilet seat down – because there were a lot of people sharing toilets now.

Q: How many families lived in your apartment?

A: Five families lived with us.

Everybody had to draw to determine who would do the cooking and who would do the cleaning. Most of the ladies had never cooked, cleaned or ironed before. I had an aunt who was an incredible cook, so she got that job. My mother was very businesslike, so she doled out the food products to be used; we had a big pantry. Everybody got jobs, and it really worked out remarkably well. The children were able to just remain children – the parents allowed that to happen.

Jews could not go out until after five, so the children went to the market late in the day. The food products that were left were pretty shady by that time. We got a lot of food from gentiles and friends, including people my father had worked with. They brought food, and it kind of worked. This whole process worked from the beginning of March until October.

Q: Did you attend school during this time?

A: No.

Q: Were you homeschooled?

A: I do not really remember. When my mother passed away eight, nine years ago, my source that held the answers to those questions was stopped. Now, I depend on a lot of information and memory, but some things are kind of pieced together.

We did do a tremendous amount of reading, so that worked out fine.

Q: What else did you do with your time?

A: The kids became very entrepreneurial. We used to buy newspapers and sell them to the people we lived with. Europeans smoked a lot, but it was hard to get cigarettes, so we would collect cigarette butts, take the burned ends off and put what little tobacco was left into a ball. Then we rolled new cigarettes out of toilet paper and sold them. We did this because we realized that our parents were working and would need some support. Those are things that made it all work. We were very excited about how we were growing up.

I did have one experience with a very good friend, a little girl, who lived in our building before it was designated as a Jewish house, and who stayed in our building afterward. I said to her, shortly after all this had happened, ”When do you want to play? Do you want to play today,” and she said she could not. ”So how about tomorrow?” I asked, and she said she could not. So I said, ”Tell me when,” and she said she ”could never play with me again.” That was her answer. I said, ”Why not?” and she said, ”I am not sure, but it is because you are Jewish.” I said, ”What does that have to do with anything?” She said she did not know, but she knew she could not play. That was the most traumatic point for me, I think, because I did not understand what she was talking about. But she did not understand either.

Q: What happened then?

A: During those months, everybody was aware of wagons (trains) taking people to camps. Those with us who were pessimistic claimed that they were concentration camps and gas chambers. Other people said that was ridiculous, that it was not possible for anybody to do that. But then they started rounding up people in the streets, and the restrictions became more serious, and by the beginning of October, they really were rounding up all the Jews.

Everybody, including my family, would have tried anything and everything to stay alive. My father was busy working out all possibilities for saving our lives. One possibility was conversion. My mother and I went to a Catholic church, and we had to go through a whole learning process in order to be converted. My father did not do this, but he insisted that my mother and I do it because, supposedly, if you were converted, you would not qualify. This turned out to be a lie because if you were a little Jewish, you were Jewish.

At one point, my parents were going to send me to a convent, another possibility for survival. But, as much as they thought my odds of survival would be better if I were in a convent, emotionally, the thought that, if something is going to happen, let it happen to all of us, kept them from doing so. So, staying together was the option they chose. It was a good thing. A lot of my friends ended up in convents, separated from their parents.

Q: And, somehow, you did all manage to stay together?

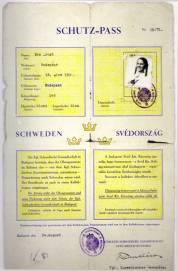

A: Yes. And somewhere along the way, my father heard about Raoul Wallenberg, and my parents and I got the Schutzpasses, and we were told where the safe house was.

Q: Do you know how your father heard about Raoul Wallenberg?

A: I think he heard about Wallenberg through the Jewish organization I mentioned earlier. Budapest was not a big city, and information was available to those who were involved in such things.

Q: Did your father ever mention Wallenberg to you or your mother?

A: Yes. Wallenberg was kind of a hero, really, from the minute he arrived – not because we knew how things were going to play out but because this fairly young man, from another country, without any ties to the Jews or to Hungary or to anything, took this task upon himself. Without any credentials except his family, he walked in there and pretended that he was important and that people should listen to him. And it worked.

Q: Did you ever see Wallenberg?

A: No, I never saw him.

Q: Do you remember what your Schutzpass looked like? Were you present when it was prepared?

A: I was not there, but my father was, and he brought them home. They looked like little passports. He was told that if we were stopped or anything, this would be a passport to safety, and they could not arrest us.

When we walked in the street, my mother had a very self-assured way about her. She did not walk around like she was scared, and she always said to me, ”Stand up straight.” The other thing she said to me was, ”Do not ever contradict me.” In other words, if somebody said, ”What is your religion?” and my mother answered, ”Catholic,” most of the time, a young child would say, ”No, I’m not. I’m Jewish.” My mother said, ”If I say it’s black, it is black – even if it is white or purple. It does not matter. You can ask me later, and I will explain to you my reasoning.” I remembered that my whole life: never to contradict my mother – which is what children do all the time. She was very rational.

My father, on the other hand, being a man, was very easily identified as a Jew since the first thing they did when they arrested people, besides asking for papers, was ask the men to drop their pants. That was the end of any argument because of circumcision. So my mother became very protective of my father, and she did all the talking.

In October, when the day came to move, my mother and father told me that we had to leave our home and that we were going to put on several layers of clothes. I had a backpack, and whatever we could carry by ourselves, we could take. We did not take a lot of stuff because we did not quite know where we were going. My biggest worry was where we were going to sleep. My parents said they did not know but not to worry, ”we are going to be together, we are going to be fine.” The only thing I put in my backpack was my pillow, which I continue to take wherever I go. That was my little object of security, along with some layers of clothing. We were not too prepared because it was October and winter was coming.

We had several people tell us that the Germans were rounding up Jews and that we were not safe anymore. There were a lot of stories. We went out and asked one person to help us, but she said that the SS were around and that she could not take a chance on taking us in. We went somewhere else, and we ended up staying there for a day or two. We stayed in basements, in attics, in people’s houses, and in the houses of gentiles who were away and, through their superintendents, gave us permission to stay; but they said that they would deny letting us stay there if they were ever confronted. My mother became extremely efficient and organized our shelters when we were still in Budapest. She was very big on organizing things and providing us with whatever we needed.

Once, we stayed at a house among the private homes in the suburbs of Buda. My father went outside one morning for a walk, and there were a lot of dead people who had been shot. My father took off their boots and brought them back to us because, when this all started, we were not prepared; the shoes we had were wearing out because of all the walking we were doing. Afterward, we used to tease my father for doing that because he was always a very polite, academic, soft-spoken person. We used to talk about what war does to people and to their behavior.

At one point, we went to the safe house. One thing I do remember is going in and it being packed like sardines. It was really scary. If you were claustrophobic, you would have walked right out. There were piles and piles of people and no provisions. My parents talked and talked, and we stayed there one night, and then we left the next day because my father was concerned that having all those Jews packed into one tiny space presented a very good opportunity for the SS to come and just kill us all at once, Schutzpasses or no Schutzpasses.

My parents thought it would be better to just go underground by ourselves, which is what we did. We owned a building, and the superintendent was somebody who worked for my father and had a high respect for my father, so we went there, and he put us in an apartment, and he would bring us trays of food. It was a very nice apartment, and it had a lot of children’s books, so I did a lot of reading. I read all the children’s classics. We listened to one of those underground radio stations in the apartment; we were getting information about what was happening in Europe.

When we were hiding in that particular building – in the apartment where we had the radio – my father had a very painful kidney stone attack, and there was a big dilemma about what to do. (He had had kidney stones before.) We certainly could not have the doctor come to us, so it was decided that my father would walk to the doctor. I remember sitting for hours, listening for him to come back. Anyhow, he came back hours and hours later, and we were all very happy. I really don’t remember what happened with the kidney stones.

Then, sometime along the way, it turned to winter, and it was cold. The allies were getting very close, and there were a lot of shootings. The Russians and the Americans were coming in, and there was some talk that the Germans were losing and that they were getting even worse about rounding up whomever they could find. They were killing as many Jews as they possibly could in case they lost the war. There was a major siege going on, and everybody was shooting, so we walked to the countryside, outside of Budapest.

We found safety with people and places to stay. We stayed mostly on farms, where the people led very simple lives, not like what we were used to. We had no beds and slept mostly on the floor. The people were very kind and let us sleep. I always slept in between my parents, so I always had that comfort.

Q: You were still in danger, though, even in the countryside, right?

A: At that point, we were not only in danger as Jews hiding from the Germans. There were also bombs flying all over the place, and we couldn’t even tell who it was doing the shooting. We tried to create as much of a shelter as we could. We kept hearing rumors that the allies were getting closer. But ”closer” was not ”here,” and it was not over.

Food became a big problem. I was extremely fussy (I used to smell everything before I even put it in my mouth), and there were not a lot of choices. One time, my mother was working at the farm, and a chicken had laid an egg, so she stole the egg, and she made me a yellow cake. I guess some flour or something had been available, but she needed the egg. She made just a little piece of yellow cake. I had always liked sweets, so that was very good.

People would share pieces of bread or things like that with us. I always liked Hungarian sausages, so my mother would cut one tiny slice of sausage and chop it up finely so that there were many, many pieces, and she made one sandwich with the little sausage. There were a lot of dead animals on the road, and a lot of people cut pieces off of the animals.

Q: Eventually, you headed back to Budapest?

A: All the Jews who had been hiding started to go back to Budapest, and so did we. But there were still a bunch of Germans hanging around. At one point, there was a firing line, and we were lined up to be shot. But a bomb was dropped nearby, and the Germans who were supposed to shoot us ran away. That was scary. It is funny because, in a child’s mind, you do not really deal with the reality. You see guns and people, but you do not totally understand it. As I said, though, I was incredibly secure in the idea that everything was going to be OK.

I mentioned to you that my grandparents came to the United States in 1939. I know that my grandmother was never really happy here. Unfortunately, she got cancer and died in 1942. My mother was extremely close to her, and she was in her 20s when my grandmother left Budapest. Anyhow, my mother made up a story that every time we saw a butterfly flying outdoors, it was my grandmother, and she was taking care of us, and it meant that everything was going to be alright. My mother was lucky – we saw a lot of butterflies. I totally bought into that story. I shared it with my daughter, so we always get very emotional about butterflies. We have a butterfly pin and all that. That was my butterfly story.

And we did survive; we got through the firing line. It was February, and we just kept walking. We were not even sure of the direction. The roads were lined with dead bodies, dead animals, and it was very cold. Then we heard rumors that the allies had arrived. Our next bad experience was with the Russians.

It is interesting: when we compared Eichmann, the ultimate gentleman who dressed like he did and knew what to wear for the best affairs, to the Russians, who were rude and vulgar, we could not think of them as our liberators. My father – I have no idea how – traveled with a bottle of cologne, still made in this country and called 4711, I think; it was like aftershave. The Russians took one look at this bottle and went for it. We did not speak Russian, but my parents had acquired a couple of words, and my father tried to explain to them that it was something people put on their faces. One Russian wasn’t buying that, and he took a sip. He spit it out and put down the bottle with a disgusted look.

Q: How much time had passed since you left your apartment in Budapest?

A: We left in October and returned in the spring. So, my personal involvement in the war and the atrocities I saw only lasted for a year, which was the shortest period of time one of the European countries involved could have experienced.

After we returned, my parents had visas and we were supposed to go visit my grandparents – my mother’s parents – but we were not able to. Basically, more and more restrictions were implemented between 1939 and 1942. Things still seemed OK, but then, after 1942, we could not go on vacations or anywhere. So we went back to our apartment.

Q: What happened when you returned to your apartment?

A: My father had said that if we got back to our apartment and there were any Germans there, he was going to kill them. I do not know how he planned to do that, but I don’t think he would have. Anyhow, nobody was there. There had been a lot of bombing, so there were holes in the walls, and the house was not exactly in the best condition.

This was now postwar. The Americans were there, and my parents began to speak with the American soldiers, which kind of helped us get information. A lot of our family was missing: cousins, aunts and uncles. My grandmother passed away when I was eight, and most of my other relatives ended up in concentration camps. But some lived through the war, and we did actually find one aunt alive. Her husband and son were dead. There had been a major massacre at the Danube on Christmas; men were called and made to take off all their clothes and face the Danube to be shot. So the blue Danube became the red Danube. My father was able to identify my uncle through his dental information. I am not sure how that worked, but a lot of people were identified by their teeth.

The next few months were a combination of putting our own lives back in some order and dealing with the issue of there being no food available. They were hanging Germans all over the place, and everybody was kind of pleased by that. The synagogue was in bad shape. The city was cleaning up all the bodies. Lots of people who couldn’t be identified were buried. The American soldiers were searching for people’s families, but unfortunately, the Americans were very anxious to get all their soldiers back home, and the Russians were happy to continue living in Budapest because life was better there than where they had come from. Now, there is actually a Wallenberg park in Budapest with a memorial tree that the actor Tony Curtis was instrumental in placing. The park also has a museum and a cemetery.

As time went by and my father opened his business, we went back to some normalcy. We thought that we would stay in Budapest and that we would go back to our normal, prewar way of life. But then, all of a sudden, the Communist party came, and all the people who had been Hungarian Nazis now became Communists. They changed their green shirts with the arrow crosses to red shirts. Anybody could get a job. My parents got a little concerned about what was going to happen, so we applied for visitors’ visas. And, even then, my parents were not totally committed to leaving because they thought that, politically, things may work out. So we packed up everything with the knowledge that if we moved to the United States and decided to stay there, they could ship our stuff to us. We left for Switzerland and came to the United States because my grandparents and my uncle had come here in 1942. My uncle was a young man then, and he had come to join the American army. After the liberation, he was actually in Europe, so he came to visit us.

Q: Where did you arrive in America?

A: We left from Dover, and we landed in New York, first class.

On the boat, my mother was very sick; she had seasickness the whole trip. But my father and I had a great time. We watched movies. My mother had a beautiful coat she used to wear, but she did not get to wear it because she got served in her cabin.

Q: Did you stay here in New York?

A: We stayed here. We got off the boat here in New York, and my grandfather got us an apartment in an apartment hotel where he was living, on West End Avenue and 95th Street. After a while, we moved into another residential hotel on 86th Street and Central Park West because we needed a little more space. Then, my parents started looking for an apartment because we decided that we were going to stay in the United States, and we told the packers, or movers, in Budapest to send us our stuff. We got our furniture, dishes and crystal. They did not send my father’s library; they kept it. So our valuable things – library stuff, paintings – they did not send. It took us a while to find an apartment because all our furniture was European and very large. We stored it for a while, and then my mother found an apartment on Riverside Drive and 75th Street. We sold a few pieces and, with the rest, furnished the apartment. It really looked lovely, traditional.

The move to the United States was harder for my parents than it was for me. We got here in the spring of 1947, and in the summer, I was shipped off to an American camp in Maine. That fall, I went to the eighth grade at a public school in the Upper West Side.

Q: Did you speak English already?

A: I spoke a little bit of English. Subsequently, I found out that the English my English nanny in Hungary had spoken was not that good. She had learned how to speak English English, not American English, and I realized that my English was not that great. It had worked in Hungary, but in school and at the camp, the kids were not only American, they had come from a whole different world. I was sort of quiet for a while.

Q: During the time that you were in Budapest after the war, did you hear anything about what happened to Raoul Wallenberg when he disappeared in January 1945?

A: The only thing I remember is that nobody knew where he was. There was a rumor that he was alive. I do not know what happened. There was no reason whatsoever for the Russians to take him. I am sure that it was not a pressing case for a lot of people because they were busy getting their own lives and memories put back together. They had to put all those memories away.

It is interesting that, 60 years later, there is more talk about the war than there was when the war ended. My family totally assimilated. My parents had an accent, so it was obvious that they had not been born here, and my parents had a lot of Hungarians friends, but I ran right off to camp and into school, and I became an instant American teenager. Not until about 15 years ago, when the Hidden Child Foundation organized and had a gathering in New York at the Marriott Hotel, did I attend something like that. It was advertised all over the place. That was the first time I got in touch with other Hungarians. Throughout all my school and college years, I had no contact with Hungarians – except my parents.

Q: What was it like to connect with other Hungarians after so many years?

A: It was incredible. I did not even want to go – my daughter read about the gathering in The New York Times Magazine and said that I should go. It was held on Memorial Day weekend, and we had already been invited to the beach by some friends. I told my husband that I did not want to mess up the whole weekend, so ”How about I leave for one day and then go back to the beach?” He said he could come back to New York with me, but I came by myself. Then I heard that Elie Wiesel was going to speak that evening, so I called my husband and asked him to please come to dinner.

The gathering was in a huge ballroom, and there were people looking for each other – they had notes. The foundation expected 200 or 300 people to attend. There were people from all over the world; there were signs for every continent. I sat at the Hungarian table. Then we had, like, a little group therapy, and people told a little bit about their stories. One of the women kind of became the leader of our group and said, ”What about gathering once a month and sharing our stories?” and that is what we did.

Q: So, the people at your monthly meetings are all Hungarian?

A: Yes. Some dropped out. Some died. But the group is interesting because there is almost a 10 years’ age difference between the oldest and the youngest members. There are people younger than me, and there are people older than me who are in their 80s. Some were only babies or a couple of years old when they were hidden, but others were not children – they were 18 years old or so.

It is a very diversified group. The common denominators are: being Hungarian, being Jewish and having been hidden. But our lives have taken different routes. Some of the people are still kosher and Orthodox, but others are not. So, because we do not have a current common denominator, we can only talk about the same topic for so long. You cannot be friendly with everybody who lives in the city, for instance, just because they live in the city; you have to have similar interests.

The group found out very early on that our children (”the next generation”) have two mindsets. One group resents their parents because they never talked about the war. The other group resents their parents because it was all they talked about (”When I was your age….”). And those children say, ”I’m sorry that happened to you, but it is not my war. I do not want to hear about it.” So it is just an interesting contrast.

Q: What was your approach for speaking to your daughter about the war?

A: I would say that I was in the middle. I did talk about the war but not a lot. One thing my daughter just recently pointed out is that I tell the overall story, but I do not go into the sentimental part, the fear. I think I even blurred some of that out. I like the glass half full rather than half empty.

I really give credit to my parents. I only have one daughter, and there was one thing I never shared with her. My father took a whole set of pictures right after the war, and they were really horrific. I gave them to the museum. I told my daughter that someday, when she grew up, I would show her the pictures. I made such a big deal out of it, and when she turned 35, I think she decided she was grown up.

I am not sure about all this sharing…. It has been 60 years, and we said ”never again,” but it has happened again and again and again. Now, because of television and CNN, we see terrific things all the time. That was just not the case in those days.

Q: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

A: I have grandchildren. I have shared stories with them. Actually, at that Hidden Child meeting, they had a wonderful library of children’s books, so I bought a lot of books as references on how to deal with relating my story to my grandchildren. It is interesting because, at this stage of my life, I almost have a need to share more with my grandchildren than I did with my daughter. I was young when I got married, and I was young when my daughter was born, and I was still busy assimilating, and somehow my war was over. It was a different world. Now, I am very conscious of the fact that I am the last generation, and after the people of my generation are gone, the stories will be gone. That is why I like to share.

CREDITS

Interview: Daniela Bajar and Nathalia Terra

Transcript: Nathalia Terra

Editing: Katie Kellerman