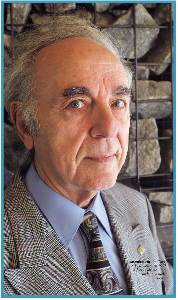

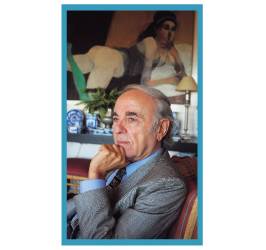

He was born in a Jewish colony in Santa Fe. He presides over the Wallenberg Foundation and has worked towards interreligious dialogue for half a century.

Baruj Tenembaum defines himself as an authentic ”Jewish gaucho.” Businessman by profession and Biblical teacher by vocation, he was born in 1933 in a colony in Santa Fe. To this day, he travels the world, fostering dialogue and closeness among people beyond their religion or beliefs, through the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, which he founded. Tenembaum’s merit is that he brought up the idea of ecumenism even before the II Vatican Council, called forth by Pope John XXIII in 1962 and closed by his successor, Paul VI, in 1965. In his conversation with EL FEDERAL, this unique social activist spoke also of his friendship with personalities such as Raúl Soldi, Jorge Luis Borges, and Antonio Quarracino.

I was born in a colony in Santa Fe called Las Palmeras, near Rafaela and Sunchales. Everyone knew everyone there. Not just amongst ourselves: when we would see a horse, we knew whose horse it was. We were too few and had very little to do. When my grandparents arrived there, and were followed by the area gauchos, they were the first to learn the lesson on living together, and respect. I grew up with the gauchos and the Polish laborers, Russians and Checks who came for the harvests, and they all followed their own tradition with total respect for others.

What was your life like at the colony?

Actually, I was born in Rosario, but after five days I was taken to the colony so my grandfather could circumcise me there. I grew up in the country. I played with the ploughs and the alfalfa. They were my toys. I learned to ride a horse, but I was not able to learn to ride a bicycle or swim, since there was no water there. My old man was a horse tamer; I think he was the only one in the Jewish colonies. And orthodox, not a very common thing in the colonies. And on top of that, I believed in God. I grew up like that, with the colts. I was very mischievous, I loved to ride a horse without a saddle, and I would not fall off. Mi parents had a small shop at the end of town. I would play around and climb onto the roof, otherwise my dad would ”spank me.” I would stay for hours there, until he promised that he would not spank me. Then I would come down. I completed my education in Buenos Aires.

What was your formation like?

I attended secondary school, graduated from the seminary of rabbinic studies, and began to study and teach the Bible. I came to understand that not only religion, but also customs and some legal aspects in Argentina, have Catholic roots. It occurred to me that the Greek and Aramaic Bible should have a place in the Christian seminaries. So I began to teach there, in full fellowship with priests and pastors. That is how we began, fifty years ago, to have the first Judeo-Christian dialogues, before Angelo Roncalli – John XXIII.

With whom did you have this inter-religious dialogue?

I was very fortunate, because I found Monsenior Ernesto Segura, the Auxiliary Bishop of Buenos Aires, and that is how this started to grow. In time, as the idea of stimulating dialogue, understanding, and knowledge expanded, so did our interreligious work.

How did you experience racial hatred?

In my colony in Santa Fe, living with the gauchos was fantastic. During World War II, the town gathered at 7 in the afternoon to listen to ”Reportes Esso” on the only old radio we had in town. They would turn it on at the last minute, since it ran on batteries, and we would hear about what was going on in Europe. There I heard for the first time the concept of hatred towards the Jews, because of what was happening in Germany. But anti-Semitism in Argentina was something I began to absorb during my adolescence, in Buenos Aires. In the country we did not know what that was. In Las Palmeras there was not a priest or a rabbi who told us to love one another, because that was spontaneous. That planted in me a love for the country and for Catholicism. And I did go through rough times, because years later I was kidnapped by the Triple A (Argentine Antisubversive Alliance) during the military dictatorship, and I had to go abroad, but I would have never considered renouncing my Argentine passport. I am from here.

The ”Triple A” accused you of ”infecting the Catholic Church.”

They were referring to my interconfessional work. At that time, Pedro Simoncini was with Channel 11, Luis Clur with Channel 13, Sergio Villaruel in Córdoba, and ”crazy” Héctor Ricardo García, with the newspaper (Crónica).They were a group of people that really stimulated this type of dialogue. When Pope Paul VI arrived in Israel in 1965, I was Director of the Israeli National Office of Tourism and it occurred to me to have a literary, Biblical contest about the papal trip. Paul VI in person ended up honoring me with a distinction for organizing the contest. I appeared a lot; I had a lot of exposure at that time. And so did artists such as Raúl Soldi, Carlos Alonzo and Jorge Luis Borges.

You were friends with Borges.

Yes. What people did not quite understand was how Borges came to join us in our interreligious dialogue. Because we would say that it was not just the religions, but also the dialogue with the people who believe, and also with those who are not fortunate enough to have faith. With Borges we founded the Argentine House in Jerusalem, in 1966.

But, specifically, why were you kidnapped?

The Triple A believed that I had information regarding some kind of international Jewish conspiracy to rule the world – a ludicrous idea. I was convinced that they were going to kill me, and that is what saved me. I was able to negotiate with them, my wife Perla ended up being taken hostage, and we convinced them to let us get out of the country. We made our home in New York, in the U.S., with a very low profile. We did not speak to anyone about what had happened to us. We had to start over, because the militaries kept all of my belongings. I took advantage of my commercial contacts and I worked in tourism. But I never abandoned my interconfessional work.

What is the Raoul Wallenberg Foundation?

Raoul Wallenberg was a young, Swedish architect, the son of a protestant family, who was a diplomat for the Swedish Embassy in Budapest, Hungary – practically the last country seized by the Germans. He had diplomatic immunity, which the Nazis respected, and he began to issue visas and documentation to Jews in order to rescue them, thus saving thousands and thousands of people. Since he sometimes had to house them, he rented houses and he said that they belonged to the embassy, thus extending diplomatic immunity to them, and he housed them there until the end of the war. It is said that it was between 80 and 130 thousand people, but what is certain is that no one in history has ever saved as many people as Wallenberg. For us he is a symbol, because there were, are, and always will be, many Wallenbergs.

What is the Foundation’s goal?

Actually, ours is the same institution that we started in the 60’s, with the spirit of seeking an encounter between cultures. We want to point out the good; find the Wallenbergs who exist around the world. My great friend, Cardinal Antonio Quarracino, asked me to build a mural close to his grave in the Metropolitan Cathedral. He said: ”So as to continue proclaiming brotherhood, as I have done all my life.” And there we put it: it is the first memorial in the world for the victims of Shoá (the Holocaust) in a Christian temple. It was built by Carlos Palarols at the altar of the Virgen de Luján (Our Lady of Luján).

How does this story continue?

The latest thing we have accomplished through the Foundation, after several years of negotiations, is Chancellor Rafael Bielsa’s agreement to sign the derogation act of the Circular 11, a secretive and discriminatory document issued in 1938,which denied access to the country to any person who was persecuted by the Nazi regime. Furthermore, we produced the movie Legado (”Legacy”), which tells the story of the Jewish colonization in Argentina, and is doing well in several international festivals. Another great challenge we face is to find the Argentine Wallenbergs. Those who saved people during the arduous 70’s, even as they put their own lives at risk. Thank God, there are many.

Translation: Jorgelina Mackey